The

plans of both governments, which had promised to join the WTO by

December 2005, did not look very realistic from the beginning. But the

bureaucrats in Moscow and Kiev frightened critics off, swearing up and

down that they would complete the negotiations in time for the Hong

Kong summit. Naturally, people started lobbying away furiously for

their special interests. But since the interests of all branches of the

economy (except the export of gas and oil, and possibly of metals) are

irreconcilable with membership in the WTO, the position of the official

negotiators became difficult in the extreme.

For they not only would have to sell their own populations down the

river (which wouldn't bother anybody in Russia or Ukraine, Orange

Revolution or no), they also would have to give over the majority of

their entrepreneurial classes, including foreign investors who have

already put money into doomed industries.

Whenever Russian membership in the WTO comes up, people mention the

automobile industry, no doubt because its representatives have been the

most vociferous in expressing their views on the government's plans.

And of course, everybody notes right off that under the long-standing

protectionist policies, the owners of the auto factories simply did not

learn to make good cars. The famous Volga is going out of production,

and the Lada gets progressively worse and more expensive as the years

go by. Yet people forget that the national auto industry has not

consisted simply of Volgas and Ladas for a very long time now. There

are Fords from the Leningrad region, Hyundais from Taganrog and a whole

series of other brand names whose cars have been assembled in Russia

for some time, just as the Ukrainians have been assembling Daewoos.

A side effect of the protectionism was that foreign corporations were

forced to develop their production in Russia. If the protectionist

policy is retained, the production of automotive component parts will

also be expanded. But the opening of these markets would spell doom for

such plans.

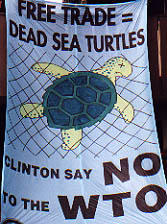

What's happening with Russia's and Ukraine's WTO membership is only one

aspect of a larger crisis within that organization, a crisis which

makes the violent protests of the South Korean farmers in Hong Kong

seem no more than a minor irritation.

The WTO's crisis is systemic. It is entirely clear that the

organization needs to change course, that the policy of liberalization

and deregulation has reached a dead end and that continuing it will not

be profitable even for those countries that pushed it through in the

first place. The Western nations understand perfectly that opening

their agricultural markets would lead not only to the disappearance of

farming but also to a whole chain of ecological and social disasters

well outside the agricultural sector. Thus, despite the small relative

weight of the farmers in the general population, their interests are

aggressively defended in both Europe and the United States.

Many Third World countries nevertheless continue to demand the opening

of Western markets, seemingly by inertia. The governments in question

are merely faithfully following the recommendations of their U.S. and

European teachers. But in practice, the strengthening of export

orientation in weakly developed economies brings them even more trouble

than it does the West. The greater part of the agricultural population

does not gain from developing exports. On the contrary, the position of

the transnational agribusinesses is strengthened at the expense of

local rural populations. Unemployment rises, internal markets are

disrupted, and the economic crisis deepens. The sole answer is to let

the West retain its protectionism, but with the condition that

everybody else gets the right to defend their own markets too.

As always happens with failed policies, the costs associated with their

continuation exceed the benefits many times over. The WTO's steering

wheel needs to be turned in the opposite direction, but structures of

this kind are simply incapable of doing that. They are doomed because

they were "imprisoned" by the strictures of a single task -- the

liberalization of markets in this instance -- and they do not have the

minimal flexibility necessary to react either to the demands of society

or even to the needs of a fairly large portion of the Western elites.

Boris Kagarlitsky is director of the Institute for Globalization Studies.

http://www.themoscowtimes.com/stories/2005/12/22/009.html

Boris Kagarlitsky

Boris Kagarlitsky